2017 St. Louis PrideFest Guide Feature: Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis

By Steven L. Brawley

Special to 2017 St. Louis PrideFest Guide

June 19, 2017: As we celebrate Pride 2017, the St. Louis LGBT History Project is excited to provide an update on a new historic initiative that will literally put St. Louis on the map.

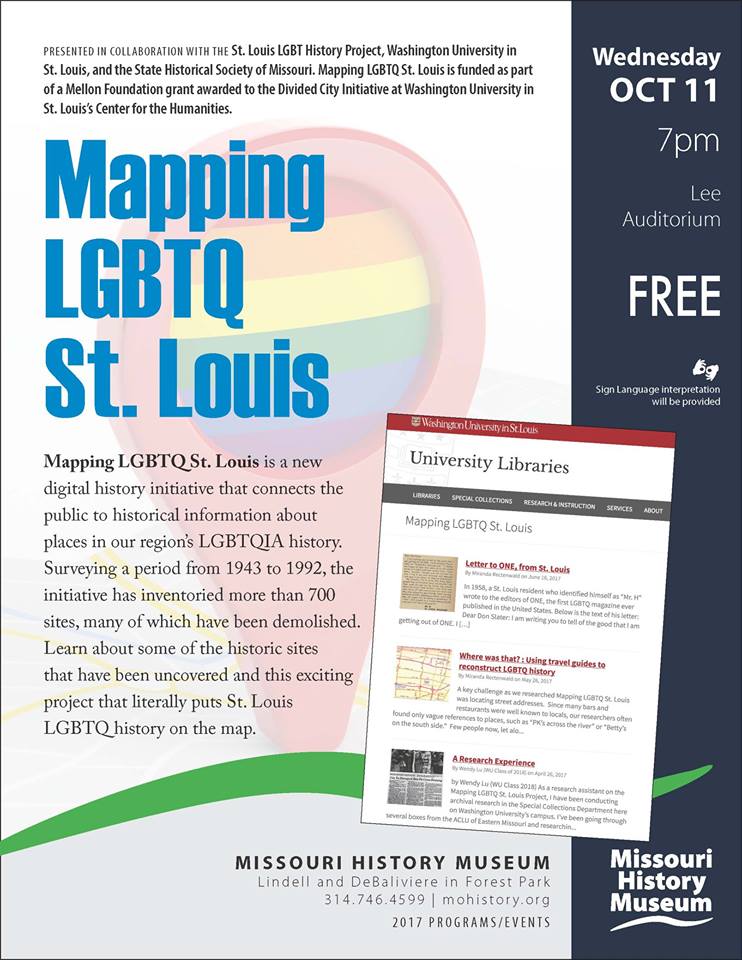

Through an innovative partnership with Washington University in St. Louis, the Missouri History Museum, and the State Historical Society of Missouri (UMSL), the Project is assisting in the development of "Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis" digital history initiative.

Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis is set to launch October 2017 with an exciting interactive website. Surveying a period from 1943 to 1992, the initiative has inventoried more than 700 LGBTQ spaces. The new map is being funded as a part of a Mellon Foundation grant awarded to the Divided City initiative at Washington University's Center for Humanities.

Since spring 2016, students, researchers, faculty, archivists, librarians, and interested people have been gathering historical information about places connected to St. Louis's LGBTQIA community. The information is being organized using GIS tools to show sites on a digital map (think Google Maps – but with history).

Ian Darnell, Ph.D. candidate University of Illinois at Chicago and St. Louis LGBT History Project researcher, says the mapping project is uncovering many lost and unknown LGBTQ places.

"I was amazed to learn how many historical LGBTQ spaces were in structures that were demolished to make way for parking lots and garages," says Darnell.

According to Darnell, one of the best examples of this pattern is the Entre Nous, an infamous gay bar in downtown St. Louis that was raided by the police in the 1950s. The building were the Entre Nous was located was torn down and replaced with the Famous-Barr parking garage in the early 1960s.

Dr. Andrea Friedman, co-director of the Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis initiative and Professor of History and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Washington University, says that finding these lost spaces has sometimes been a challenge.

"In the early years, many community organizations were identified only by a post office box or phone number, which meant we couldn't identify their locations for the map," says Dr. Friedman. "Because St. Louis is so marked by racial division, it has been harder to find the more informal or less visible social spaces that, if St. Louis is like other cities, may have been the center of African American LGBTQ life, such as residences, after-hours places, or places of worship."

Darnell says the research task was made much easier by posing questions to the members of the St. Louis LGBT History Project's Facebook group.

"Many of the older members of the group were firsthand witnesses to St. Louis's LGBT history," Darnell says. "In a number of cases, they were able draw on their memories to confirm, supplement, or even correct written records. I want to thank everyone who contributed to these discussions online. Their help was invaluable."

"The beauty of mapping is that it helps make clear the ways a community is made through (or divided by) space. Users of the new map will be able to see how the St. Louis region's LGBTQ community changed over time. It will showcase where the bars, the bathhouses, and the drag balls were, and track the emergence of other community spaces such as restaurants, shops, community centers, places of worship, dances, self-help groups, the sites of protest and policing, even the places where St. Louisans met for sex," says Dr. Friedman. "There will be links to photographs, news clippings, oral history transcripts, and other documents to tell the stories behind the dots on the map."

Darnell believes the map will inform the community about St. Louis' LGBTQ history, contributions, and influence.

"I think it will show that LGBTQ people have had an impact on nearly every part of the St. Louis region—truly, "we are everywhere." But it will be equally clear that LGBTQ social spaces and activism have tended to be concentrated in certain parts of the metropolitan region, and that shifts in the geography of St. Louis's LGBTQ spaces were related to the region's history of racial segregation, socioeconomic inequality, and urban decline and renewal. St. Louis's LGBTQ history isn't somehow apart from the city's wider history -- it's embedded in everything else."

Learn more about Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis.

Learn more about the St. Louis LGBT History Project.

The 2017 St. Louis PrideFest Guide is available in the Riverfront Times or at the June 23-25 St. Louis PrideFest.

Saint Louis University Student Video Project

June 12, 2017: During the spring of 2017, the Project was happy to provide assistance to Saint Louis University students TK Smith and Elizabeth Eikmann in producing a special video for a class project. The video includes interviews with Sayer Johnson, Ian Darnell, Steven Brawley, Erise Williams Jr., and many others. The interviews were also donated to the Project for future reference and research.

Last Call: Speculating Disappearing Queer Space by Elizabeth Eikmann and TK Smith, Saint Louis University describes how gay bars have a deep history of serving the LGBTQ community beyond mere social interaction. For many, gay bars have been sites for LGBTQ persons to mobilize in the face of social, political, and health crises, fostering a space for community and solidarity with one another. Gay bars have also functioned as spaces where community members can freely express, perform, and negotiate identity and proclaim affection, love, and sexual attraction to whomever they wish without fear of persecution in the process. But have gay bars always been spaces of safety, security, and representation for all? Who has been excluded? And where do those excluded from the gay bar go?