By Ian Darnell

September 10, 2015: In August, the St. Louis LGBT History Project obtained historical records that officially document police raids on local gay bars. More than sixty years old, these previously unstudied sources offer a fascinating glimpse of gay nightlife in the 1950s. The records also shed light on the changing relationship between queer people and St. Louis's police.

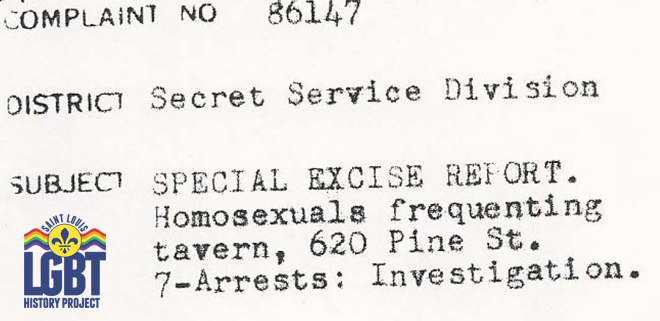

It's not news that in decades past the police sometimes raided St. Louis's lesbian and gay bars. Older members of the local LGBT community have long told stories about these incidents. Up until now, however, the Project had been unable to locate any written records of these raids. Uncovering these documents was the result of many hours of detective work in several local archival collections, culminating with a Sunshine Law request to the Records Division of the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department.

The records consist of three related police reports dated August 27, 1954. They detail a series of coordinated and apparently simultaneous raids conducted around midnight on three downtown bars. Two of these bars, the Entre Nous and Uncle John's, were located across the street from one another on the 600 block of Pine Street (parking garages now occupy the sites of both bars). The third bar, Al's, was located nearby at 115 North 9th Street (now on the site of AT&T Center skyscraper). We know that several other lesbian and gay bars were in operation in the St. Louis area at the time, but these do not seem to have been raided that night.

About one dozen law enforcement officials participated. The reports indicate that the police raided the bars because they "had received numerous complaints that homosexuals were frequenting [them]." It was against state liquor regulations for bar owners to allow "immoral persons to loiter on the premises" of their establishments. This provision effectively made it illegal to run a lesbian or gay bar. At the time, it was also illegal to have sex with a person of the same sex or to dress in the clothing of the opposite sex.

According to the reports, twenty-one people were arrested and taken to the district police station for questioning. These included the bartender at Al's and a man who played piano for customers at Uncle John's. In the reports, everyone who was arrested is listed as male. However, it is possible that some of the people arrested during the raids might not have been male, but instead were what we would think of today as trans women or genderqueers. We do know that some of the bars' customers wore makeup and had long, bleached-blond hair.

The people arrested ranged in age from 18 to 59, but most were in their twenties and early thirties. Most lived in the city of St. Louis, although some were from nearby suburbs, and one was visiting from a small town in southern Illinois. They worked in a number of occupations, including laborer, factory worker, musician, and accountant. Notably, everyone arrested was white. Evidence suggests that in the 1950s white-owned lesbian and gay bars in St. Louis often refused service to black customers, which was in line with the Jim Crow culture of the time.

The report includes a brief statement from each arrested person. The police appear to have interrogated the arrestees about their sexual habits, with many statements indicating an interest in "sodomy by mouth" or "sodomy by rectum." Some of the statements give us an idea of the LGBT slang of the era. Oral sex was called a "French job," and gay bars were called "fruit joints" or "queer joints."

Taken together, the statements suggest how important these three downtown bars were for many queer people in St. Louis. Many of those arrested said that they had been coming to the bars for years, visited them frequently, and had met friends and sexual partners there. At these little bars downtown, located in discreet spots and easily accessible by public transit, queer people from around the city could drink, listen to music, chat, and "let their hair down" with people who were like them.

Some of the statements also suggest that the people arrested that day felt that they were being treated unfairly by the police. Here we can see what we might think of as the beginnings of a political consciousness. Some of the arrested people insisted that "no one ever objected to their actions or their presence" at the bars, and one man said that he could not help being a homosexual. Another man said that "he is going to continue to be a homosexual regardless of any Police action as he deems his acts to be his own affair." Elsewhere in the United States at around the same time, the Mattachine Society and other early LGBT groups were beginning promote ideas similar to these.

These three police reports provide a unique window on LGBT life in St. Louis in the 1950s. At the time, queer people could find each other and build community in St. Louis's "fruit joints"—but by patronizing these establishments they also faced the threat of arrest and abuse at the hands of the police. This situation helped set the stage for the beginnings of LGBT political activism in St. Louis in the 1960s.

The St. Louis LGBT History Project will continue to piece together the story of queer people in the Gateway City by gathering and analyzing sources like these 1954 police reports. Contribute to the Project's work by serving as a volunteer researcher or by donating your own historically significant documents, photographs, and artifacts. Do you have your own story to tell about trouble with the police or other aspects of St. Louis's LGBT history? Contact the St. Louis LGBT History Project today.